The City of Darkness |

|

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Notice

Message: Only variables should be passed by reference

Filename: pages/site.php

Line Number: 13

- Also Known As:Carrières de Paris

- Genre:Cemetery / Crypt, Colliery / Mine

- Comments: 327

- Built:N/A

- Opened:N/A

- Age:N/A

- Closed:N/A

- Demo / Renovated:N/A

- Decaying for:N/A

- Last Known Status:Abandoned

Photo © 2013 Tom Kirsch, opacity.us

Paris Catacombs History

An extensive network of tunnels exist underneath the street of Paris, however unlike most cities, these passages were not meant for pipes, sewers or electricity. They are all part of a long-forgotten quarry that was re-discovered in 1774, and subsequently used as the final resting place for an estimated six million bodies from the overflowing city cemeteries, making it the world's largest grave. A small portion of the network has been built for spectators to visit and see the artfully arranged bones, but the vast majority of the old mining tunnels are off-limits to the public, and some of these abandoned passages still contain human remains.

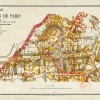

The excavations underneath Paris began in the late 13th century, harvesting the deposits of Lutetian Limestone, which was used as a building material as well as gypsum (most commonly used in "plaster of paris"). These mines burrowed underneath the sparsely populated suburbs of the city until sometime in the 16th century, when they were abandoned and simply forgotten about. When Paris expanded its borders in the 17th century, architects were confronted with massive underground galleries that would compromise the structure's foundations, and budgets would often be depleted by reinforcement work. A major road called Rue d'Enfer (literally, "Hell Street," now called Avenue Denfert-Rochereau) suffered a major collapse in 1774, sending a house and the street tumbling into a 100-foot deep hole of the former mine.

King Louis XVI's response to this collapse was the creation of a department in charge of inspecting, maintaining, and repairing underground foundations of royal buildings and national roadways, called the Inspection Générale des Carrières (IGC), formed in 1777. As the centuries of mining under Paris was mostly forgotten about, the vast network of tunnels needed to be explored, mapped, and tested for stability, leading to a series of explorations by official architects. When a portion of the roadway needed to be reinforced, the date of the work and the name of the road was engraved into the solid masonry of the support underground.

As the old quarry tunnels were being mapped and explored, Paris faced another problem: the city's cemeteries were overflowing. Cimetière des Saints-Innocents (Holy Innocents' Cemetery) was essentially a mass-grave site located in the heart of the metropolis. When the in-ground pits were full, charniers (charnel houses for bodies) were built along the cemetery walls to hold more human remains stacked inside. The unsanitary conditions of the rotting corpses inside the charniers was the driving force behind two edicts from the king to move the cemetery, but the church resisted, who profited from burial fees. Only when a wall collapsed under the weight of one of the mass graves occurred in 1780, a law passed which stated no interments would be accepted inside any city cemetery.

Despite the new ordinance people still snuck bodies into these cemeteries, and so their removal was necessary, but there was the problem of where to place the remains of millions of people. Police Lieutenant-General Alexandre Lenoir, who was directly involved with the IGC, firmly believed these newly-rediscovered quarry passages were the best option, and this became law in 1785. A section of the passageway under the street Tombe-Issoire was chosen to retain the bodies from five city cemeteries: Saints-Innocents, the largest with about 2 million bodies, Saint-Étienne-des-Grès, one of the oldest, Errancis Cemetery, which mostly held victims of the French Revolution, Madeleine Cemetery, and Notre-Dame-des-Blancs-Manteaux. The catacombs underneath Paris currently hold an estimated six million human remains. [Morbid Note: once the stacked bodies were removed from the cemeteries (Saints-Innocents had grown to a depth of 60 feet), great mounds of fat were left behind, preserved by the lack of oxygen due to the close packed nature of the corpses; this human fat was handed over to local boilers to produce candles and soap which was then sold to Parisians.]

For the next two years, a nightly procession of wagons covered in black cloth made their way from Saints-Innocents to a passageway that was dug to lead into the quarry. At first, the bones were simply dumped inside the passages, but the head of the mine inspection service, Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury, undertook a project to arrange the bones into a mausoleum for public display beginning in 1810. Along with artistically arranged bone walls, the catacombs featured decorations and headstones from Saints-Innocents, a display of minerals found underneath Paris, and a display of various skeletal deformities found while the bones were moved. The ossuary was walled off from the rest of the mines for the visitors' safety.

Over the years entrances have been discovered or made into the old quarry tunnels, and the clandestine spaces used for running black market goods, secret storage spaces, and some public works, such as civil defense shelters. The complex is so large that when Nazi troops occupied the city, the quarry contained both a German bunker and the Headquarters of the Free French Forces in the 1940s.

The 1950s and beyond lead into an era of party-goers and others who feverently explored, mapped and documented the passages, known as cataphiles. The catacombs were largely ignored by police until around 1970 when an overhauled IGC began to implement police patrols below ground, sealing entrances, and blocked various passages by building walls and poured concrete "injections" into the tunnels. Despite these barriers, vast tracts of the tunnels remain accessible. In 2004, police discovered an entire movie theater in one of the underground galleries, complete with electricity, projection equipment, cinema screen, seats, and a fully stocked bar.

Although many have had a good time under the streets partying or exploring, the catacombs can be quite dangerous; even armed with detailed maps, one can get lost very quickly. In 1793 Philibert Aspairt, the doorkeeper of a hospital which lies above the catacombs, became hopelessly lost in the tunnels and wasn't found until 11 years after his disappearance (his tomb remains at the spot he was found). More recent explorers have been rescued after being lost for days in the 186 miles (300km) of tunnels with no cell phone service. In 1999, liquid sand injections from the IGC almost trapped a group explorers inside one of the caverns. Many passages lie at or below the water table and flood regularly and without warning, and of course there is always the danger of sudden fontis (collapse). For these reasons, the police have deemed these tunnels off limits and issue high fines for being caught here.

The official catacombs museum still operates today, and one can view the stacked bones and curiosities collected from the early 19th century here. The off-limits areas, sometimes referred to as the quarries (Carrières de Paris), can be accessed through various manholes, cellars and other out-of-the-way places, however their entrances are often kept closely guarded among cataphiles and change often as police seal them upon discovery.