The Tamarack Lodge had a humble beginning as a six-room boarding house way back in 1903. Its name was derived from a Native American term for the black larch trees found in the area. Beginning in 1927, the lodge began expanding to become a fully-fledged Catskill resort. Successively owned by generations of the Levinson family, the Tudor-style resort eventually comprised of 300 rooms on 400 acres of land. The "Playtorium" theater featured live performances by bands such as Cream, The Who, Janis Joplin and Jerry Lewis. Guests could also take up horseback riding, golf, or swimming in Tamrack's indoor or outdoor pools. Like many resorts in the Borscht Belt, the Tamarack struggled at times. The resort was eventually shuttered in 2000 but did not languish for long. A massive fire in April of 2012 leveled most of the buildings on site.

]]>

The Tamarack Lodge had a humble beginning as a six-room boarding house way back in 1903. Its name was derived from a Native American term for the black larch trees found in the area. Beginning in 1927, the lodge began expanding to become a fully-fledged Catskill resort. Successively owned by generations of the Levinson family, the Tudor-style resort eventually comprised of 300 rooms on 400 acres of land. The "Playtorium" theater featured live performances by bands such as Cream, The Who, Janis Joplin and Jerry Lewis. Guests could also take up horseback riding, golf, or swimming in Tamrack's indoor or outdoor pools.

Like many resorts in the Borscht Belt, the Tamarack struggled at times. The resort was eventually shuttered in 2000 but did not languish for long. A massive fire in April of 2012 leveled most of the buildings on site.

]]>

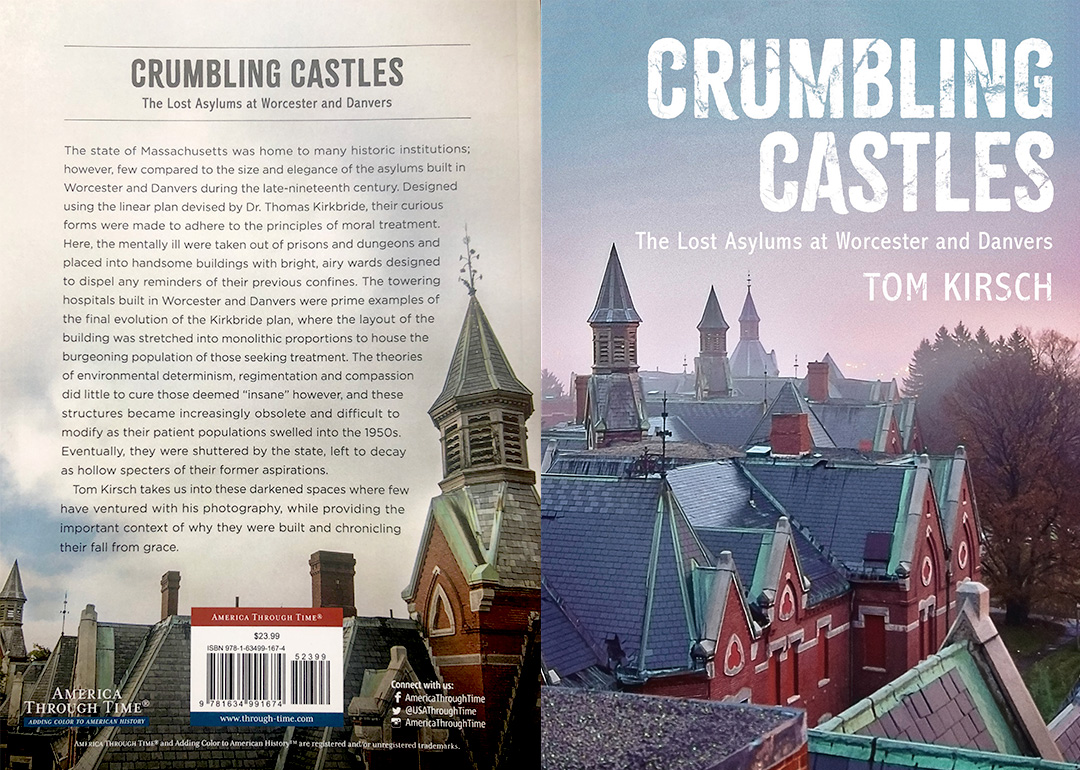

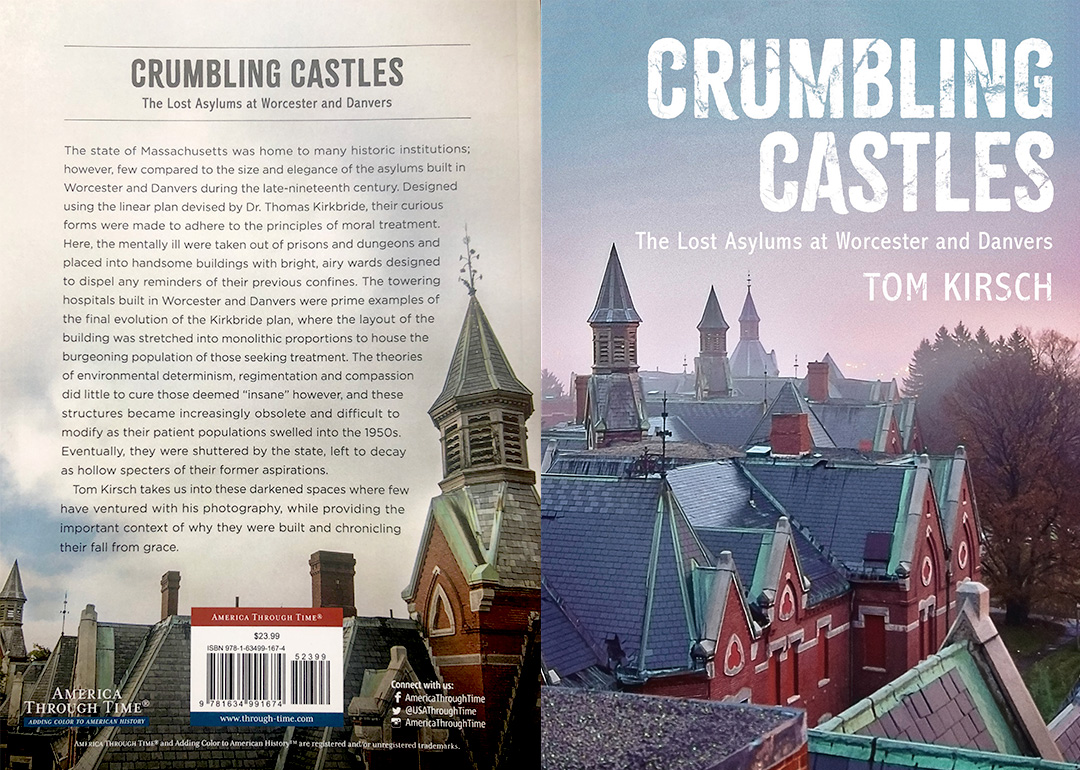

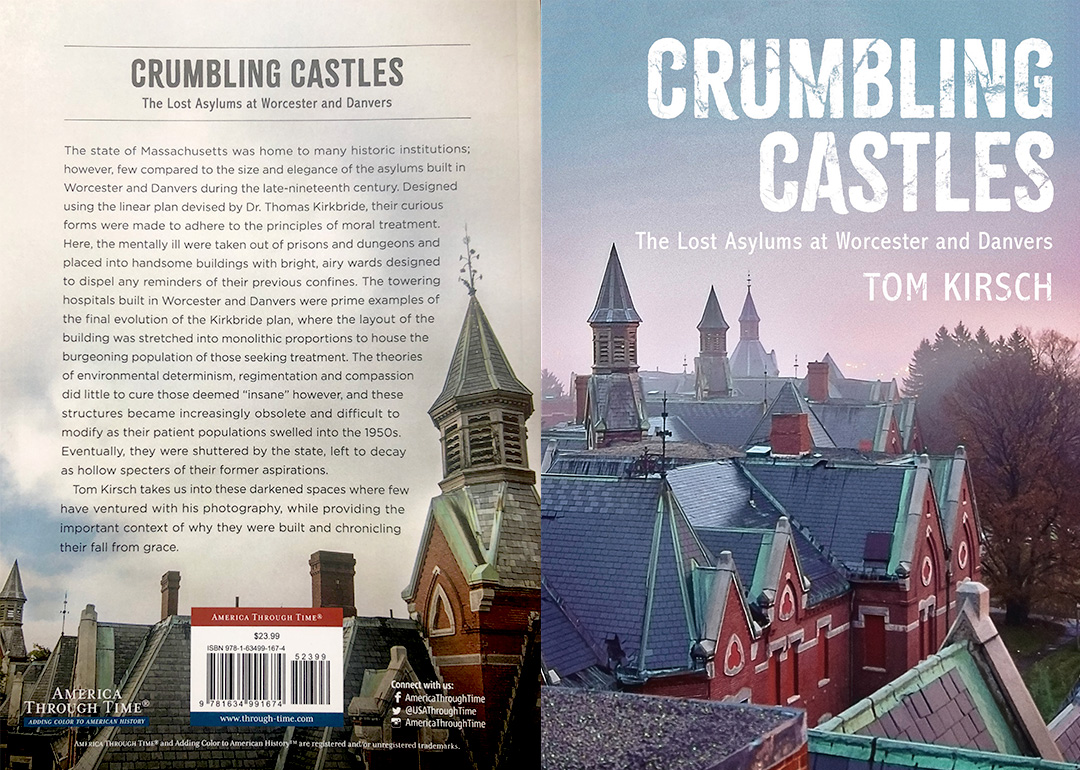

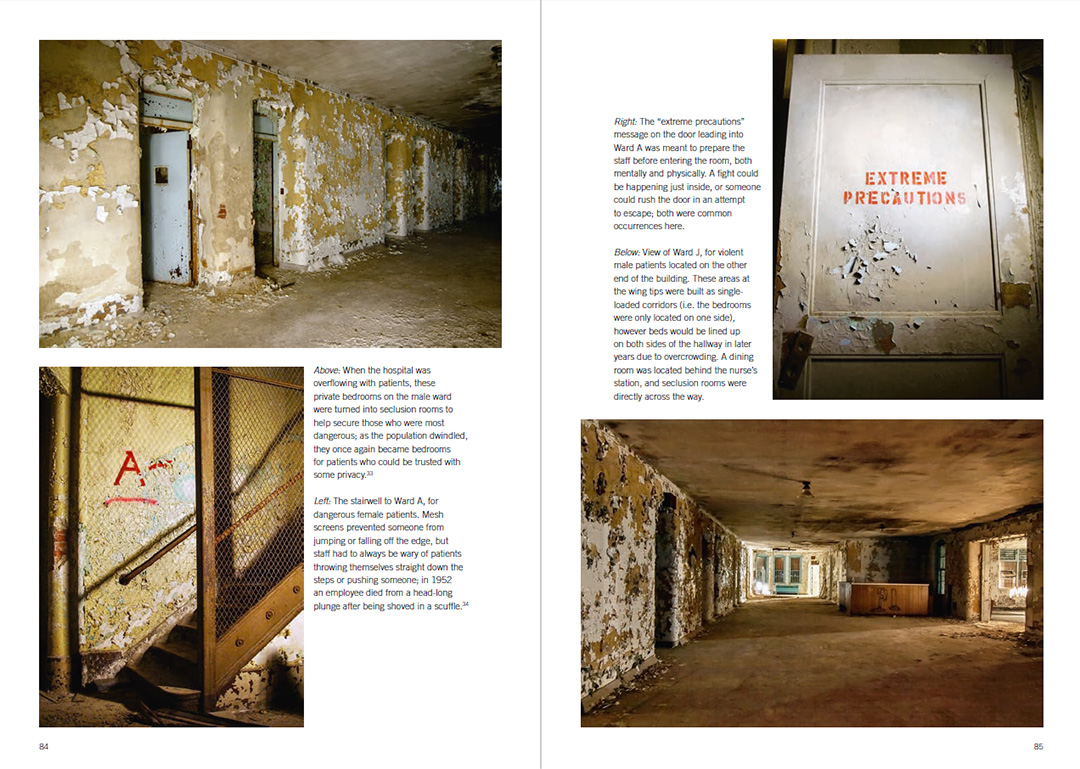

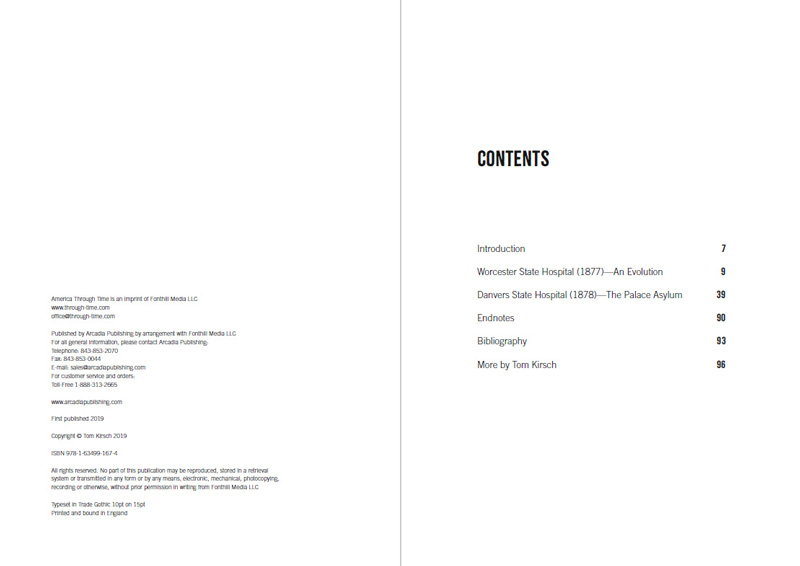

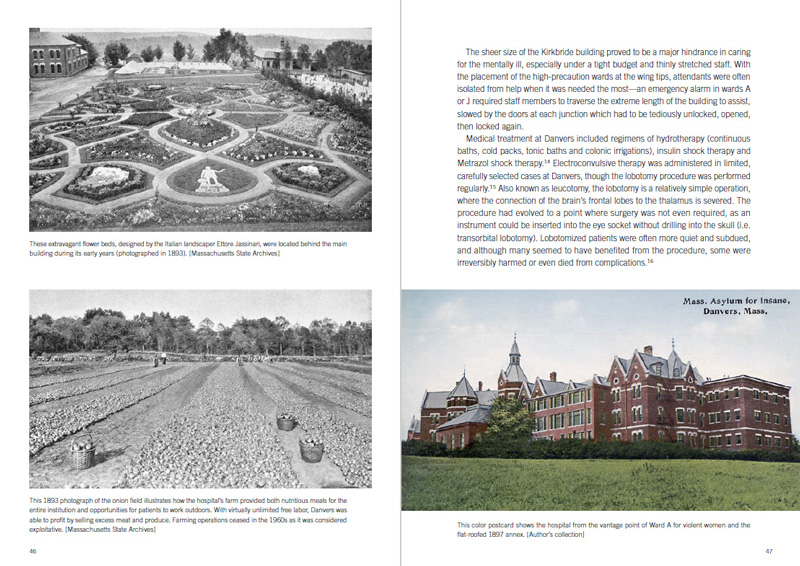

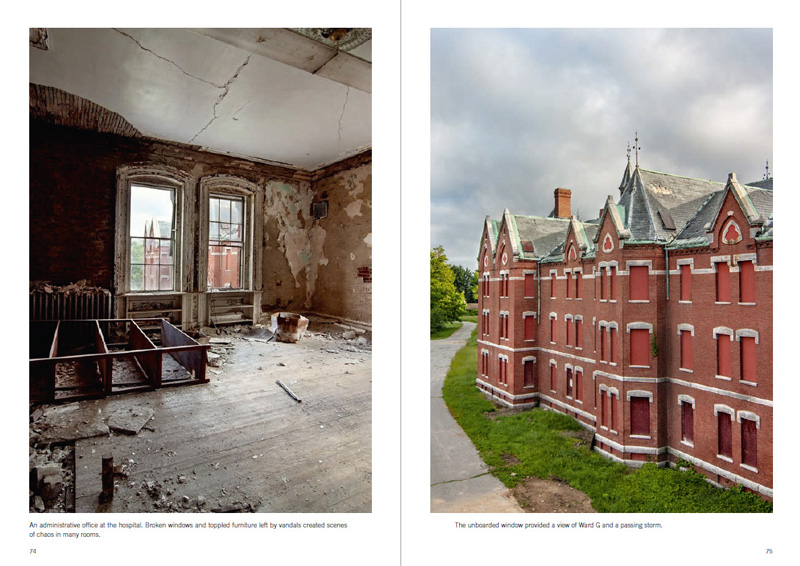

Happy to announce the release of my second book, Crumbling Castles: The Lost Asylums at Worcester and Danvers. This book continues an exploration of early Massachusetts asylums based on Dr. Kirkbride’s linear plan.

]]>

Happy to announce the release of my second book, Crumbling Castles: The Lost Asylums at Worcester and Danvers. This book continues an exploration of early Massachusetts asylums based on Dr. Kirkbride’s linear plan.

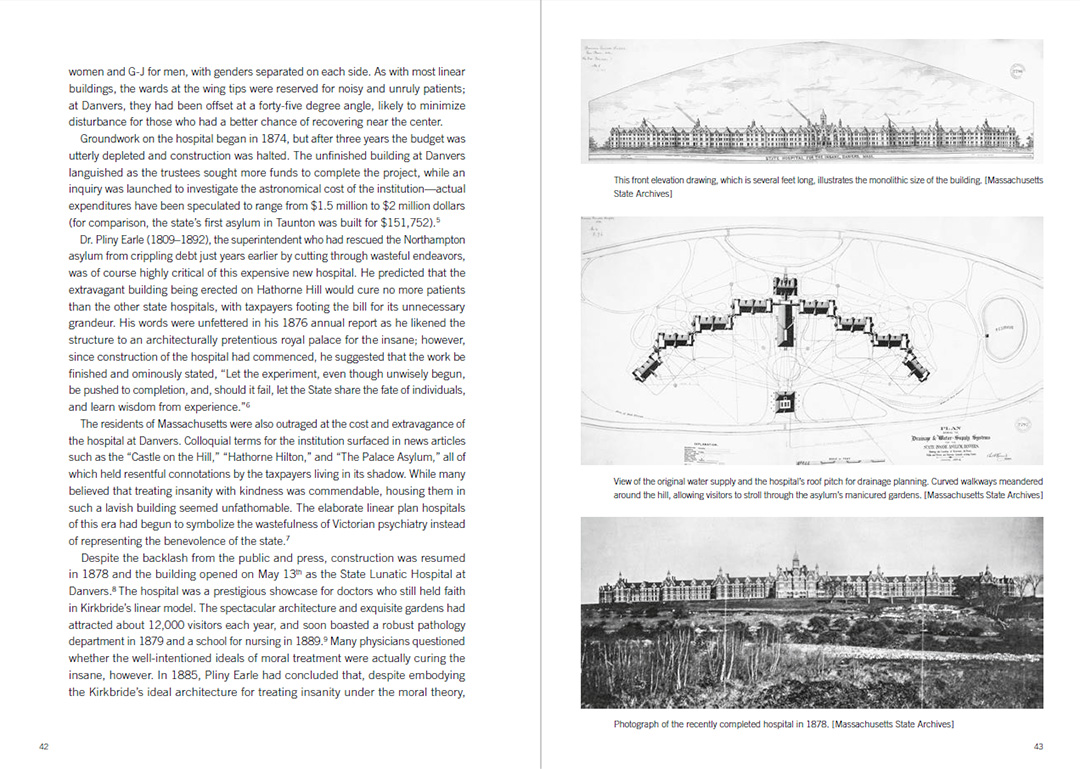

The late 19th century saw these monolithic plans becoming even larger and more grandiose as doctors sought to house the growing number of mentally ill. These two institutions exemplified the pinnacle of extravagant asylum building and design. The incredibly expensive High Victorian Gothic hospital at Danvers managed to outrage many in the psychiatric field and those taxpayers living under its imposing shadow, and thus ended the use of Kirkbride’s model in the Commonwealth. By the 1980s they were both discarded by the state and left to rot, too big and expensive to rehabilitate. After decades of neglect, they were some of the most incredible ruins to explore.

You can purchase it on Amazon here, or visit CrumblingCastles.com for more information.

This historic rail car was built by the Pullman Company in 1914, during a time known as the "Gothic period" of heavyweight passenger cars. Originally known as car No. 450, it operated as a flagship dining car for the New York Central Railroad. Designed as a 6-axle Diner Class D-74 model, it is a significant example of pre-WWII streamlined passenger car design. The car was retrofitted with air conditioning in the 1930s. It operated for NYC up until the 1950s, when the company retired most of their heavyweight equipment in an effort to streamline operations. The cash-strapped Delaware and Hudson Railway purchased the car to replace their old composite (wood and steel) carriages, where it continued to operate as the D&H 154 for some years. In the 1960s the aging car was sold once again to the Empire State Railway Museum where it operated under the High Iron Railway Company. Riding over Central Railroad of New Jersey tracks, the car was used in "steam safaris," where passengers could re-live the luxury of early railroad travel; passengers were even served meals using the car's kitchen to complete the experience. These excursions helped introduce the concept of reusing historic railroad equipment for recreation and tourism. In 1969, the car was transferred to Essex CT to join the newly founded Connecticut Valley Railroad Company. In 1971, it was painted dark green, re-numbered 154, and given the name Lion Gardiner, from the first settler in New York. The car began showing signs of deterioration in the kitchen floor, as well as problems due to the old air conditioning system and burst water pipes. It was mothballed in the Essex woods around 1976. Ten years later, it was pulled onto some disused tracks in Kingston NY, where it was once again left abandoned. Sitting on the derelict rail line next to the Lion Gardiner were Erie Lackawanna MU (multiple unit) cars, also built by Pullman, which were used for commuter service in New Jersey. These cars were powered by electrified overhead wires instead of steam or diesel locomotives. Also known as "Edisons," they were inaugurated in 1930 when Thomas Edison drove the first train from Hoboken to Montclair to promote large scale usage of DC current. Edison would have been dismayed to know that the lines were re-electrified using AC power and thus the DC cars were subsequently put out of service in 1984. As for the Lion Gardiner, despite being the last heavyweight dining car in existence, it seemed doomed to be cut up for scrap due to the cost of renovations. In December of 2015 however, the car was placed on a trailer and hauled out West, presumably for restoration. The fate of the MU cars in unclear. Video of the coaches moving for the first time in 15 years can be viewed here, as well as footage of the Lion Gardiner being pulled over the Hurley Mountain Road crossing here (after it was cleaned up a bit and primed red to stop the rust).

]]>

This historic rail car was built by the Pullman Company in 1914, during a time known as the "Gothic period" of heavyweight passenger cars. Originally known as car No. 450, it operated as a flagship dining car for the New York Central Railroad. Designed as a 6-axle Diner Class D-74 model, it is a significant example of pre-WWII streamlined passenger car design. The car was retrofitted with air conditioning in the 1930s.

It operated for NYC up until the 1950s, when the company retired most of their heavyweight equipment in an effort to streamline operations. The cash-strapped Delaware and Hudson Railway purchased the car to replace their old composite (wood and steel) carriages, where it continued to operate as the D&H 154 for some years.

In the 1960s the aging car was sold once again to the Empire State Railway Museum where it operated under the High Iron Railway Company. Riding over Central Railroad of New Jersey tracks, the car was used in "steam safaris," where passengers could re-live the luxury of early railroad travel; passengers were even served meals using the car's kitchen to complete the experience. These excursions helped introduce the concept of reusing historic railroad equipment for recreation and tourism.

In 1969, the car was transferred to Essex CT to join the newly founded Connecticut Valley Railroad Company. In 1971, it was painted dark green, re-numbered 154, and given the name Lion Gardiner, from the first settler in New York. The car began showing signs of deterioration in the kitchen floor, as well as problems due to the old air conditioning system and burst water pipes. It was mothballed in the Essex woods around 1976. Ten years later, it was pulled onto some disused tracks in Kingston NY, where it was once again left abandoned.

Sitting on the derelict rail line next to the Lion Gardiner were Erie Lackawanna MU (multiple unit) cars, also built by Pullman, which were used for commuter service in New Jersey. These cars were powered by electrified overhead wires instead of steam or diesel locomotives. Also known as "Edisons," they were inaugurated in 1930 when Thomas Edison drove the first train from Hoboken to Montclair to promote large scale usage of DC current. Edison would have been dismayed to know that the lines were re-electrified using AC power and thus the DC cars were subsequently put out of service in 1984.

As for the Lion Gardiner, despite being the last heavyweight dining car in existence, it seemed doomed to be cut up for scrap due to the cost of renovations. In December of 2015 however, the car was placed on a trailer and hauled out West, presumably for restoration. The fate of the MU cars in unclear.

Video of the coaches moving for the first time in 15 years can be viewed here, as well as footage of the Lion Gardiner being pulled over the Hurley Mountain Road crossing here (after it was cleaned up a bit and primed red to stop the rust).

]]>

A psychiatric hospital near the city of Rovigo, Italy was first proposed in 1897, but due to budgets and failure to gain approval by local authorities the project was delayed for decades. In 1906, construction of the asylum finally commenced in the town of Granzette, however upon its completion in 1914, World War I broke out and the hospital buildings were used exclusively by the army. The institution was left in shambles as warfare had ravaged the area, but reconstruction commenced in 1925 to finally open the hospital for psychiatric care. The Rovigio asylum was officially opened on March 20, 1930 and dedicated to King Vittorio Emanuele III. Several Neo-classical buildings were arranged in a radial pattern adopted from British asylum construction, though Granzette lacked the connecting corridors found in English institutions. Two nested horseshoe-shaped roads were used instead, with all buildings facing a central chapel. Like many large institutions of its day, the campus resembled a quiet town, isolated from the rest of the community. A boundary wall encompassed the buildings and was described as a barrier between "the city of healthy people from the city of fools." It was not in total isolation however, as the hospital gates were swung open one day a year for the procession of Corpus Domini, where patients participated in public parades, though well guarded and separated from visitors. The peace and quiet of this institution was considered essential for recovery. A large fountain featuring two putti (cherubs) playing in a large seashell was created by a patient in the 1930s and installed amid the tree-lined streets. An agricultural colony was established to provide both food for the patients and occupational therapy work. The hospital's magazine, published by its patients, was entitled La Canavera; the word choice was explained as follows in a 1964 edition: "to remember the environment that hosts us ..., to tell us about our childhood, our rivers, the humid fields of fog, of the wind whistling through the thick branches of the Polesine poplars ... a weak thing ... as light as the flight of a kite: the canavera." The hospital struggled with overcrowding for most of its active years. It was built for a maximum of 400 patients, though it typically held an average of 700 inside its walls. Ergotherapeutic methods of treatment were introduced at the asylum by Florentine doctor Vincenzo Chiarugi, where hot baths and massage therapy were used to attempt to soothe the agitated mind. Intrusive therapies such as insulin shock and electroshock were also extensively used, During the second World War, many of the hospital's staff were sent to the front lines to fight the allied powers, leaving the psychiatric hospital with very few doctors or nurses. The situation became critical in 1943-1945, when the entire institution was reduced to only one doctor and the mortality rate spiked at 12.54%. German troops commandeered several buildings for military purposes and rumors of gold and other Nazi treasures stashed within the walls and basements have circulated ever since. In the mid-1950s and 1960s, the agricultural colony was eliminated and funds were acquired to modernize parts of the hospital, which included a new neurological unit. In 1978, Law 180 took effect and began to empty all of Italy's psychiatric hospitals, including Granzette. It was slowly downsized until 1995, when all remaining patients were transferred to the community of Canalnuovo. In 1998, plans to revive the campus into a cancer treatment center were proposed but ultimately scrapped. Recent work has been done to secure the property and several buildings are used for local events, art exhibitions, and a historical museum. Much information here has been retrieved from Redazione Biancoenero.

]]>

A psychiatric hospital near the city of Rovigo, Italy was first proposed in 1897, but due to budgets and failure to gain approval by local authorities the project was delayed for decades. In 1906, construction of the asylum finally commenced in the town of Granzette, however upon its completion in 1914, World War I broke out and the hospital buildings were used exclusively by the army. The institution was left in shambles as warfare had ravaged the area, but reconstruction commenced in 1925 to finally open the hospital for psychiatric care. The Rovigio asylum was officially opened on March 20, 1930 and dedicated to King Vittorio Emanuele III.

Several Neo-classical buildings were arranged in a radial pattern adopted from British asylum construction, though Granzette lacked the connecting corridors found in English institutions. Two nested horseshoe-shaped roads were used instead, with all buildings facing a central chapel. Like many large institutions of its day, the campus resembled a quiet town, isolated from the rest of the community. A boundary wall encompassed the buildings and was described as a barrier between "the city of healthy people from the city of fools." It was not in total isolation however, as the hospital gates were swung open one day a year for the procession of Corpus Domini, where patients participated in public parades, though well guarded and separated from visitors.

The peace and quiet of this institution was considered essential for recovery. A large fountain featuring two putti (cherubs) playing in a large seashell was created by a patient in the 1930s and installed amid the tree-lined streets. An agricultural colony was established to provide both food for the patients and occupational therapy work. The hospital's magazine, published by its patients, was entitled La Canavera; the word choice was explained as follows in a 1964 edition: "to remember the environment that hosts us ..., to tell us about our childhood, our rivers, the humid fields of fog, of the wind whistling through the thick branches of the Polesine poplars ... a weak thing ... as light as the flight of a kite: the canavera."

The hospital struggled with overcrowding for most of its active years. It was built for a maximum of 400 patients, though it typically held an average of 700 inside its walls. Ergotherapeutic methods of treatment were introduced at the asylum by Florentine doctor Vincenzo Chiarugi, where hot baths and massage therapy were used to attempt to soothe the agitated mind. Intrusive therapies such as insulin shock and electroshock were also extensively used,

During the second World War, many of the hospital's staff were sent to the front lines to fight the allied powers, leaving the psychiatric hospital with very few doctors or nurses. The situation became critical in 1943-1945, when the entire institution was reduced to only one doctor and the mortality rate spiked at 12.54%. German troops commandeered several buildings for military purposes and rumors of gold and other Nazi treasures stashed within the walls and basements have circulated ever since.

In the mid-1950s and 1960s, the agricultural colony was eliminated and funds were acquired to modernize parts of the hospital, which included a new neurological unit. In 1978, Law 180 took effect and began to empty all of Italy's psychiatric hospitals, including Granzette. It was slowly downsized until 1995, when all remaining patients were transferred to the community of Canalnuovo. In 1998, plans to revive the campus into a cancer treatment center were proposed but ultimately scrapped. Recent work has been done to secure the property and several buildings are used for local events, art exhibitions, and a historical museum.

Much information here has been retrieved from Redazione Biancoenero.

]]>

The strange concrete formations in Apple Valley, California are the vestiges of a dream conjured up by a man named Lonnie Coffman. Owning a home nearby in the 1970s, he hired Air Force serviceman Gregory L. Wicker to help build the dinosaurs on a defunct golf course using chicken wire, rebar and concrete. The prehistoric park eventually encompassed four acres with as many as 30 dinosaurs. The project was halted for an unknown reason some years later and was left to decay. Many of the unique and sometimes bizarre looking creatures have since begun to crumble. Many of their hollow bodies have become homes for snakes, wasps and bees. The creatures are located on private property next to some homes, so please be respectful and cautious if visiting.

]]>

The strange concrete formations in Apple Valley, California are the vestiges of a dream conjured up by a man named Lonnie Coffman. Owning a home nearby in the 1970s, he hired Air Force serviceman Gregory L. Wicker to help build the dinosaurs on a defunct golf course using chicken wire, rebar and concrete. The prehistoric park eventually encompassed four acres with as many as 30 dinosaurs. The project was halted for an unknown reason some years later and was left to decay.

Many of the unique and sometimes bizarre looking creatures have since begun to crumble. Many of their hollow bodies have become homes for snakes, wasps and bees. The creatures are located on private property next to some homes, so please be respectful and cautious if visiting.

]]>

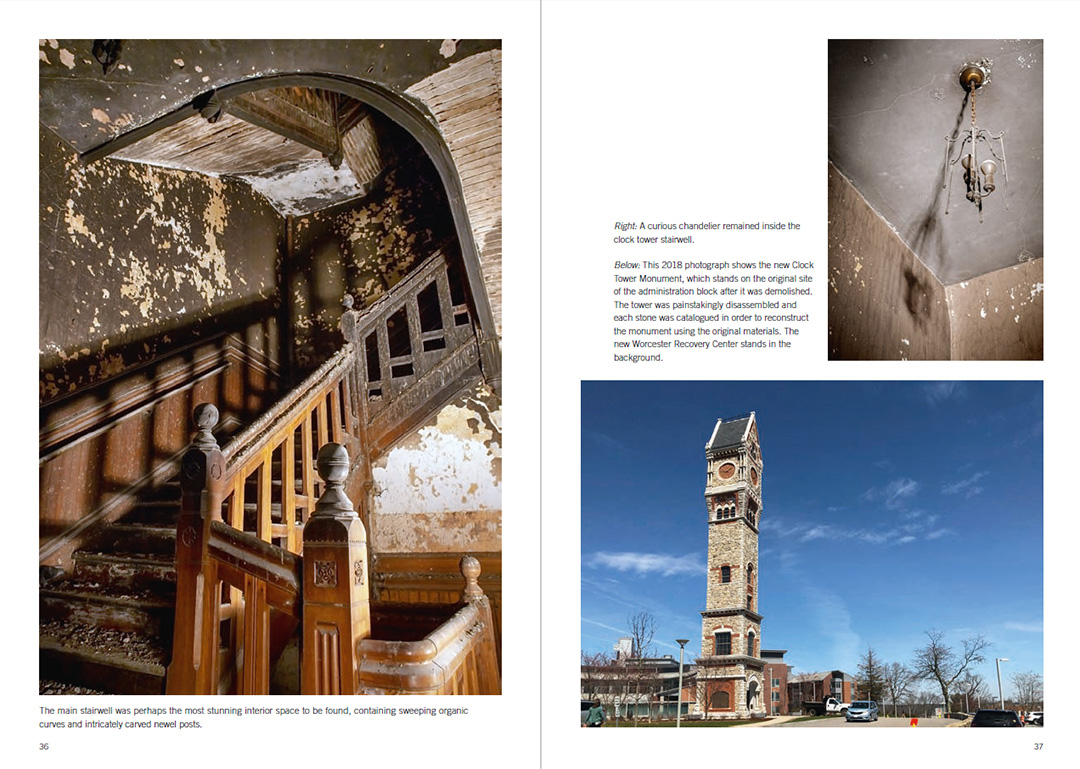

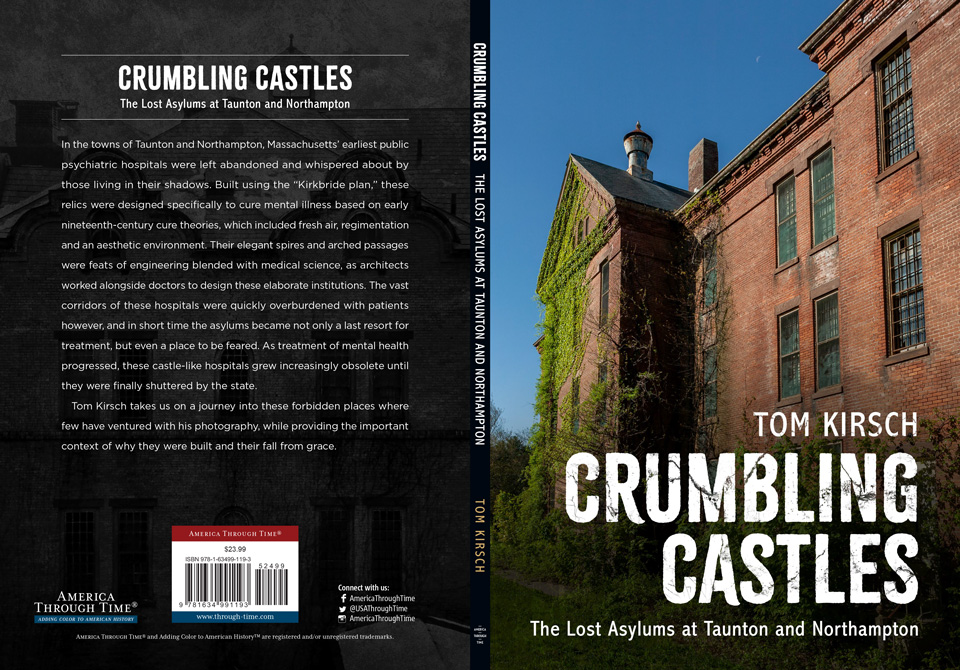

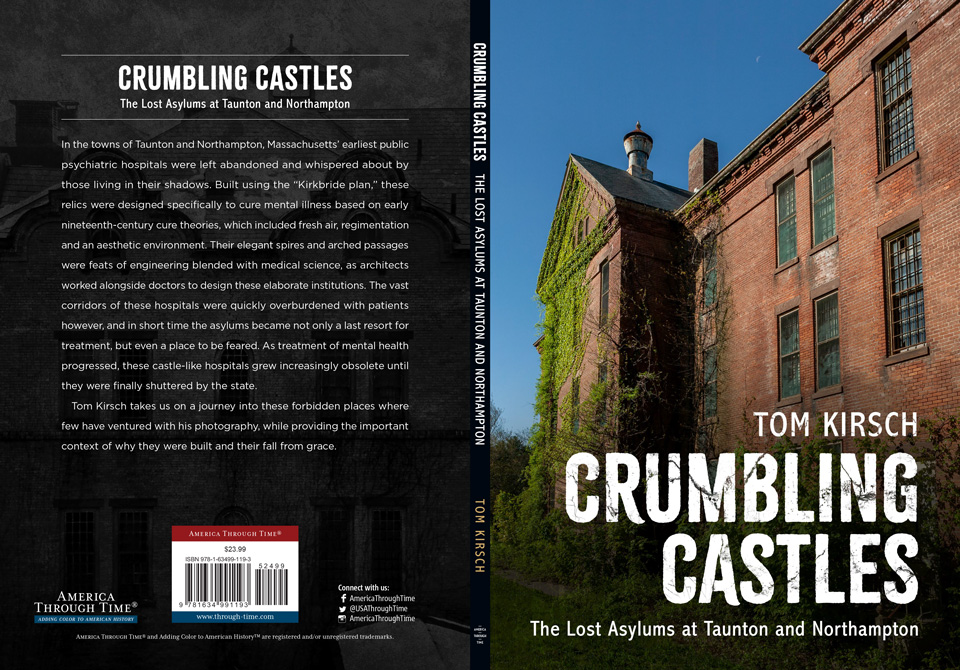

I'm happy to announce my first publication, Crumbling Castles: The Lost Asylums at Taunton and Northampton. This 96-page book focuses on the Commonwealth's first two psychiatric hospitals to use the linear (Kirkbride) plan. These early hospitals were established to cure insanity using architecture, compassion and regimentation. The book covers some of the hospital's history, followed by my photographs.

]]>

I'm happy to announce my first publication, Crumbling Castles: The Lost Asylums at Taunton and Northampton (Massachusetts). This 96-page book focuses on the Commonwealth's first two psychiatric hospitals to use the linear (Kirkbride) plan. These early hospitals were established to cure insanity using architecture, compassion and regimentation. The book covers some of the hospital's history, followed by my photographs. Published by Arcadia/Fonthill Media, it's available on Amazon here.

After spending many hours at the state archives and poring over old annual reports, I've realized even more how every state hospital has an incredibly intricate history. Though they suffered many of the same problems and demises, each had their own kind of personality, made up of various staff members and residents. Their stories are complex and deep, and each certainly merits their own book that unravels their inner workings. With limited space and budget, I hope this book sheds at least some light on their past.

I'm also working on a second volume which covers the larger, modified Kirkbride hospitals in Worcester in Danvers, due to be released in October. More information on the series can be found at crumblingcastles.com.

Massachusetts' first public reform school for juvenile offenders was established in 1848 on Lake Chauncy in Westborough, where inmates were housed in a single building known as simply "State Reform School." The boys were given school and religious instructions while also performing manual labor in an attempt to "reform" their behavior and return them as contributing members of society. Their ability to work the fields, prepare food, clean, and craft or repair items was utilized to keep the institution running on a minimal budget, much like how the asylums for the insane were run at the time. Inmates were released when they were considered "reformed" or until they reached the age of 21. After a particularly bad riot in 1878 and negative press concerning abuse of the boys made headlines, it was decided that the single congregate-style building was not suited for this purpose and deemed a failure. It was decided to move the institution to a new campus where smaller, detached buildings served various functions; known as the cottage system, it had begun to gain popularity among the designers of many state institutions during this time. The old reform school was renovated to become the Westborough Insane Hospital in 1886. A farm on Powder Hill was purchased in 1885 for the new cottage institution, not far from the original school building on the opposite side of Lake Chauncy. The new campus was called Lyman School for Boys, named after the Boston philanthropist Theodore Lyman. The institution consisted of cottage-style dormitories, an auditorium/chapel building, administrative and support buildings, as well as a working farm. The dormitories were brick structures that could hold about 30 boys in each, and segregated the boys based on their age and ability. Showers and locker rooms were located in the basement, the first and second floors were for meetings and daily activities, and the top floor was called the "ramp," where students slept. Each dormitory was administered by a married couple, known as the master and matron; this was intended to instill a sense of family for the boys, many of whom had been orphaned or rejected by their own families (interestingly, the married staff method of supervision in cottages was also attempted for the insane at Worcester State Hospital, but rejected). The masters and matrons at Lyman cottages were assisted by a school teacher and a laundress. Despite the fact that some boys had committed serious crimes, the Lyman School campus was rather open and resembled a preparatory school rather than a prison. Doors were unlocked and there were no walls or fences. Instead of iron bars and barriers, residents were trained to stay at the facility using a combination of education, honor and threat of punishment. Although security was lax, daily life at the school was strict and heavily regimented. Religious education was required (the only options were Catholic or Protestant), as was learning a trade from a skilled tradesman - this was not optional. The boys worked the farm, cooked the food, repaired the buildings and did the laundry; these skills were intended to be used once released. The school grew throughout the Great Depression, and eventually expanded to over 700 acres of land and eight cottages. Buildings were given colloquial names such as Lyman Hall, Chauncey, Overlook, Sunset, Hillside, Wachusett, Worcester, Westview, Elms and Oak. A large print shop produced much of the official Commonwealth documents and government stationary. During World War II, many of the boys and employees were drafted or enlisted, leaving those few that remained to tend to the kitchens and coal-fed boilers to keep the institution running. After World War II, the population at Lyman had started to take on a tougher demeanor with many violent, mentally unstable, and illiterate young men. The younger and less-troubled students were moved elsewhere as social services became available, and during the 1950s and 1960s Lyman saw an influx of older offenders who were involved in gangs, drugs, alcohol, and weapons. The master-matron model was discontinued during this time due to practicality, replaced by a single cottage master. In 1953 the farming program was also halted, as trade unions and advocacy groups saw the work as nothing more than free child labor. The fields went fallow and the animals were sold off as the boys were relegated to pass the time doing household chores or watching television. Despite the discontinuation of these programs, the school still burgeoned with young men, prompting the addition of a central cafeteria and school building. There were over 590 students at Lyman by 1960, with some even sleeping underneath beds in the small cottages due to overcrowding. The 1960s were hectic years at Lyman as efforts to de-institutionalize the facility sought to empty the school, while administrators wrested with bureaucratic turmoil and disorganization. In 1971, girls were admitted to two cottages and the facility was co-educational for the first time, making it even more difficult for staff to maintain control. Without vocational training or sufficient education programs, many residents were considered lost causes, never to be returned to normal society. Students at the school often caused disturbances that required police intervention to maintain control. Runaways were common, and the sound of the fire whistle was often heard as students escaped the premises. The threat of being sent to the Lyman School was often used by parents to scare their children into behaving. Around 1971-1972 the Lyman School was closed for good, leaving 265 acres of land and a number of buildings behind. Some of the cottages have been re-purposed, however a few structures remain abandoned and in various states of deterioration.Sources include Richard Johnson's page (who also authored a book about the school), this article by Glenn Parker, and this footage found in 2018, narrated by Rev. Bob Brown, the former Lyman chaplain and administrator.

]]>

Massachusetts' first public reform school for juvenile offenders was established in 1848 on Lake Chauncy in Westborough, where inmates were housed in a single building known as simply "State Reform School." The boys were given school and religious instructions while also performing manual labor in an attempt to "reform" their behavior and return them as contributing members of society. Their ability to work the fields, prepare food, clean, and craft or repair items was utilized to keep the institution running on a minimal budget, much like how the asylums for the insane were run at the time. Inmates were released when they were considered "reformed" or until they reached the age of 21.

After a particularly bad riot in 1878 and negative press concerning abuse of the boys made headlines, it was decided that the single congregate-style building was not suited for this purpose and deemed a failure. It was decided to move the institution to a new campus where smaller, detached buildings served various functions; known as the cottage system, it had begun to gain popularity among the designers of many state institutions during this time. The old reform school was renovated to become the Westborough Insane Hospital in 1886.

A farm on Powder Hill was purchased in 1885 for the new cottage institution, not far from the original school building on the opposite side of Lake Chauncy. The new campus was called Lyman School for Boys, named after the Boston philanthropist Theodore Lyman. The institution consisted of cottage-style dormitories, an auditorium/chapel building, administrative and support buildings, as well as a working farm. The dormitories were brick structures that could hold about 30 boys in each, and segregated the boys based on their age and ability. Showers and locker rooms were located in the basement, the first and second floors were for meetings and daily activities, and the top floor was called the "ramp," where students slept. Each dormitory was administered by a married couple, known as the master and matron; this was intended to instill a sense of family for the boys, many of whom had been orphaned or rejected by their own families (interestingly, the married staff method of supervision in cottages was also attempted for the insane at Worcester State Hospital, but rejected). The masters and matrons at Lyman cottages were assisted by a school teacher and a laundress.

Despite the fact that some boys had committed serious crimes, the Lyman School campus was rather open and resembled a preparatory school rather than a prison. Doors were unlocked and there were no walls or fences. Instead of iron bars and barriers, residents were trained to stay at the facility using a combination of education, honor and threat of punishment. Although security was lax, daily life at the school was strict and heavily regimented. Religious education was required (the only options were Catholic or Protestant), as was learning a trade from a skilled tradesman - this was not optional. The boys worked the farm, cooked the food, repaired the buildings and did the laundry; these skills were intended to be used once released.

The school grew throughout the Great Depression, and eventually expanded to over 700 acres of land and eight cottages. Buildings were given colloquial names such as Lyman Hall, Chauncey, Overlook, Sunset, Hillside, Wachusett, Worcester, Westview, Elms and Oak. A large print shop produced much of the official Commonwealth documents and government stationary. During World War II, many of the boys and employees were drafted or enlisted, leaving those few that remained to tend to the kitchens and coal-fed boilers to keep the institution running.

After World War II, the population at Lyman had started to take on a tougher demeanor with many violent, mentally unstable, and illiterate young men. The younger and less-troubled students were moved elsewhere as social services became available, and during the 1950s and 1960s Lyman saw an influx of older offenders who were involved in gangs, drugs, alcohol, and weapons. The master-matron model was discontinued during this time due to practicality, replaced by a single cottage master. In 1953 the farming program was also halted, as trade unions and advocacy groups saw the work as nothing more than free child labor. The fields went fallow and the animals were sold off as the boys were relegated to pass the time doing household chores or watching television. Despite the discontinuation of these programs, the school still burgeoned with young men, prompting the addition of a central cafeteria and school building. There were over 590 students at Lyman by 1960, with some even sleeping underneath beds in the small cottages due to overcrowding.

The 1960s were hectic years at Lyman as efforts to de-institutionalize the facility sought to empty the school, while administrators wrested with bureaucratic turmoil and disorganization. In 1971, girls were admitted to two cottages and the facility was co-educational for the first time, making it even more difficult for staff to maintain control. Without vocational training or sufficient education programs, many residents were considered lost causes, never to be returned to normal society. Students at the school often caused disturbances that required police intervention to maintain control. Runaways were common, and the sound of the fire whistle was often heard as students escaped the premises. The threat of being sent to the Lyman School was often used by parents to scare their children into behaving.

Around 1971-1972 the Lyman School was closed for good, leaving 265 acres of land and a number of buildings behind. Some of the cottages have been re-purposed, however a few structures remain abandoned and in various states of deterioration.

Sources include Richard Johnson's page (who also authored a book about the school), this article by Glenn Parker, and this footage found in 2018, narrated by Rev. Bob Brown, the former Lyman chaplain and administrator.

]]>

The former state hospital in Westborough Massachusetts was originally the site of as the first public reform school for juvenile offenders in the United States. Simply called “State Reform School,” it was comprised of a single large building designed to house and attempt to correct the behavior of young miscreants using manual labor and schooling in both moral and religious instruction. It was unknown if training such a large number of young miscreants under one roof would actually work, and the project was considered an experiment by administrators. Architects Elias Carter of Springfield and James Savage of Southborough were employed to design a building which emanated strength and security without the unpleasantness of the appearance of a prison, and designed an Italianate-style brick building with symmetrical towers and Greek Revival accents. The State Reform School was opened in November, 1848. Inmates were held at the institution until they were deemed “reformed,” or reached the age of 21 years old where they were released. With an unlimited supply of free labor, the institution was able to support itself using its inmates to farm and cook the food, wash the laundry, clean the wards and make supplies ranging from shoes to furniture (as was also customary in state mental hospitals up through the 1950s). The school’s population swelled since its opening, prompting a large expansion to the building in 1848, and by 1858 there were over 590 inmates. In 1859, a massive fire set by one of the boys engulfed much of the building. As repairs were undertaken, many inmates were housed in an old mill while older boys were sent to the “nautical branch,” which consisted of sailing vessels out at sea, where the inmates would work and be instructed. Reconstruction of the school resulted in the creation of a “correctional addition,” which was essentially a prison for the most ill-behaved older boys. A riot broke out in 1878, and after rumors of cruel and unusual punishment began to stream out to the press in the ensuing years, the congregate-style reform school was considered a failed experiment by the legislature. It was not wholly discontinued however, and instead moved a few miles away to become the Lyman School for Boys, where a cottage-style system was employed which would make handling such a large number of inmates easier. In addition to the negative press about the reform school, the state of Massachusetts was also being scrutinized over its state asylums as well. The elaborate Kirkbride-style buildings built in Worcester (1877) and Danvers (1878) were considered by many to be a colossal boondoggle and waste of taxpayer money (bitterly called “palaces for the insane” by critics). To make the situation worse, these massive and expensive asylums were were not able to house all of those being committed at the time, and the state's public hospitals continued to overflow with patients. Thus, the old reform school in Westborough seemed an ideal place to establish a new state hospital - money could be saved by using some of the existing buildings on campus, which had already been designed as a penal institution. The scenic views of Lake Chauncy and hilltop location were also extremely favorable, in that it conformed to the popular idea that an idyllic environment was essential to curing mental illness at the time. George Clough of Boston was hired to remodel the site to be used as a hospital for the insane in 1884. Some of the old school was demolished and a new section was appended to the original main building, which included a large wing extending to the east, creating common areas such as the chapel and dining hall, and beyond that was a new administration building. An H-shaped building was erected to the north for housing committed patients, and connected to the main complex via hallways with small elegant “conservatories." These pseudo-separated structures were telling of changing attitudes in psychiatric hospital design, where smaller detached buildings were preferred over monolithic Kirkbride layouts - Danvers would be the last linear plan asylum built in the state. An innovative model for state hospitals was implemented at Westborough during the renovation, which was the congregate dining hall. At older hospitals, most patients were fed in their wards by bringing food throughout the building in carts from the main kitchen building, which proved to be tedious and inefficient. The new model could feed the entire hospital at once by having patients move through the campus into a communal dining hall, where they were supervised while they ate. Congregate dining was adopted at the state’s later hospitals in Foxborough (1889), Medfield (1896) and Waltham (1930), and most of the older state hospitals also followed suit with retrofits and new structures. The institution opened as the Westborough Insane Hospital in December of 1886, taking in 204 patients from the crowded hospitals in Taunton, Northampton, Danvers and Worcester. Dr. N. Emmons Paine was recruited from the State Homeopathic Asylum for the Insane in Middletown NY, where he served as Westborough’s first superintendent. Unlike other administrators, he fully embraced homeopathy as an attempt to cure mental illness. Westborough followed the unique and sometimes bizarre treatments employed at Middletown, which included massage, hydrotherapy, plenty of rest (even if the patient was unwilling), and specialized diets of hypnotics and sedatives. Though the hospital’s methods were controversial, especially of enforced bedrest, the hospital touted a relatively high recovery rate compared to the other state hospitals into the turn of the century. A Nurse’s School was established at Westborough in 1891, and the first female doctor at the hospital was appointed as assistant physician in 1893. Several buildings were added during this period, including a mortuary, staff housing, and Talbot House, a striking Colonial Revival building designed by Rand, Taylor, Kendall and Stevens (Rand also designed the iconic Kirkbride building at Worcester). Two satellite colonies for quiet chronic patients were established on the south shore of Lake Chauncey, which were the Warren Farm Colony for Men (1903) and the Richmond Colony for Women (1903). Wards I and J for chronic disturbed patients and a large kitchen building were added to the main complex in 1906 using narrow passages to connect them. The property expanded to over 650 acres, much of it used for farming to keep the hospital’s food supply freshly stocked until the program was ended in the 1970s. The institution was renamed Westborough State Hospital in 1907 in a statewide initiative to drop words that had developed a negative connotation (such as “asylum” and “insane”). Like many other state hospitals across the country, Westborough entered a steep decline by the 1940s due to overcrowding. In 1945, the patient population reached 1,730 though its capacity was only 1,332. Most doctors and attendants had left to fight overseas in World War II, and this inadequate staffing resulted in the death of some as several criminally insane women murdered their fellow patients. These issues were somewhat remedied with new buildings constructed into the 1950s. Westborough reached its peak population in 1959 with 2,100 patients and 800 staff. Deinstitutionalization efforts in the 1970s began to quickly empty the hospital, and by 1984 there were only 260 patients in the vast complex. Unused portions of the campus were closed off and left to decay. Westborough State Hospital officially closed its doors in 2010, with remaining patients and services relocated to the new psychiatric hospital built in Worcester. Westborough State Hospital is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and its future is uncertain.

]]>

The former state hospital in Westborough Massachusetts was originally the site of as the first public reform school for juvenile offenders in the United States. Simply called “State Reform School,” it was comprised of a single large building designed to house and attempt to correct the behavior of young miscreants using manual labor and schooling in both moral and religious instruction. It was unknown if training such a large number of young miscreants under one roof would actually work, and the project was considered an experiment by administrators. Architects Elias Carter of Springfield and James Savage of Southborough were employed to design a building which emanated strength and security without the unpleasantness of the appearance of a prison, and designed an Italianate-style brick building with symmetrical towers and Greek Revival accents. The State Reform School was opened in November, 1848.

Inmates were held at the institution until they were deemed “reformed,” or reached the age of 21 years old where they were released. With an unlimited supply of free labor, the institution was able to support itself using its inmates to farm and cook the food, wash the laundry, clean the wards and make supplies ranging from shoes to furniture (as was also customary in state mental hospitals up through the 1950s). The school’s population swelled since its opening, prompting a large expansion to the building in 1848, and by 1858 there were over 590 inmates.

In 1859, a massive fire set by one of the boys engulfed much of the building. As repairs were undertaken, many inmates were housed in an old mill while older boys were sent to the “nautical branch,” which consisted of sailing vessels out at sea, where the inmates would work and be instructed. Reconstruction of the school resulted in the creation of a “correctional addition,” which was essentially a prison for the most ill-behaved older boys. A riot broke out in 1878, and after rumors of cruel and unusual punishment began to stream out to the press in the ensuing years, the congregate-style reform school was considered a failed experiment by the legislature. It was not wholly discontinued however, and instead moved a few miles away to become the Lyman School for Boys, where a cottage-style system was employed which would make handling such a large number of inmates easier.

In addition to the negative press about the reform school, the state of Massachusetts was also being scrutinized over its state asylums as well. The elaborate Kirkbride-style buildings built in Worcester (1877) and Danvers (1878) were considered by many to be a colossal boondoggle and waste of taxpayer money (bitterly called “palaces for the insane” by critics). To make the situation worse, these massive and expensive asylums were were not able to house all of those being committed at the time, and the state's public hospitals continued to overflow with patients. Thus, the old reform school in Westborough seemed an ideal place to establish a new state hospital - money could be saved by using some of the existing buildings on campus, which had already been designed as a penal institution. The scenic views of Lake Chauncy and hilltop location were also extremely favorable, in that it conformed to the popular idea that an idyllic environment was essential to curing mental illness at the time.

George Clough of Boston was hired to remodel the site to be used as a hospital for the insane in 1884. Some of the old school was demolished and a new section was appended to the original main building, which included a large wing extending to the east, creating common areas such as the chapel and dining hall, and beyond that was a new administration building. An H-shaped building was erected to the north for housing committed patients, and connected to the main complex via hallways with small elegant “conservatories." These pseudo-separated structures were telling of changing attitudes in psychiatric hospital design, where smaller detached buildings were preferred over monolithic Kirkbride layouts - Danvers would be the last linear plan asylum built in the state.

An innovative model for state hospitals was implemented at Westborough during the renovation, which was the congregate dining hall. At older hospitals, most patients were fed in their wards by bringing food throughout the building in carts from the main kitchen building, which proved to be tedious and inefficient. The new model could feed the entire hospital at once by having patients move through the campus into a communal dining hall, where they were supervised while they ate. Congregate dining was adopted at the state’s later hospitals in Foxborough (1889), Medfield (1896) and Waltham (1930), and most of the older state hospitals also followed suit with retrofits and new structures.

The institution opened as the Westborough Insane Hospital in December of 1886, taking in 204 patients from the crowded hospitals in Taunton, Northampton, Danvers and Worcester. Dr. N. Emmons Paine was recruited from the State Homeopathic Asylum for the Insane in Middletown NY, where he served as Westborough’s first superintendent. Unlike other administrators, he fully embraced homeopathy as an attempt to cure mental illness. Westborough followed the unique and sometimes bizarre treatments employed at Middletown, which included massage, hydrotherapy, plenty of rest (even if the patient was unwilling), and specialized diets of hypnotics and sedatives.

Though the hospital’s methods were controversial, especially of enforced bedrest, the hospital touted a relatively high recovery rate compared to the other state hospitals into the turn of the century. A Nurse’s School was established at Westborough in 1891, and the first female doctor at the hospital was appointed as assistant physician in 1893. Several buildings were added during this period, including a mortuary, staff housing, and Talbot House, a striking Colonial Revival building designed by Rand, Taylor, Kendall and Stevens (Rand also designed the iconic Kirkbride building at Worcester). Two satellite colonies for quiet chronic patients were established on the south shore of Lake Chauncey, which were the Warren Farm Colony for Men (1903) and the Richmond Colony for Women (1903). Wards I and J for chronic disturbed patients and a large kitchen building were added to the main complex in 1906 using narrow passages to connect them. The property expanded to over 650 acres, much of it used for farming to keep the hospital’s food supply freshly stocked until the program was ended in the 1970s. The institution was renamed Westborough State Hospital in 1907 in a statewide initiative to drop words that had developed a negative connotation (such as “asylum” and “insane”).

Like many other state hospitals across the country, Westborough entered a steep decline by the 1940s due to overcrowding. In 1945, the patient population reached 1,730 though its capacity was only 1,332. Most doctors and attendants had left to fight overseas in World War II, and this inadequate staffing resulted in the death of some as several criminally insane women murdered their fellow patients. These issues were somewhat remedied with new buildings constructed into the 1950s. Westborough reached its peak population in 1959 with 2,100 patients and 800 staff.

Deinstitutionalization efforts in the 1970s began to quickly empty the hospital, and by 1984 there were only 260 patients in the vast complex. Unused portions of the campus were closed off and left to decay. Westborough State Hospital officially closed its doors in 2010, with remaining patients and services relocated to the new psychiatric hospital built in Worcester. Westborough State Hospital is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and its future is uncertain.

]]>

The establishment of Rest Haven began with the old Schuylkill County Almshouse, a single building erected in 1833. The almshouse was a kind of jail for the infirm, poor, elderly, insane, epileptic, criminals, and those with developmental disabilities - basically a place for those "unwanted" in society at that time. Conditions were atrocious, as can be imagined by housing these many types of people under one roof. A written account from 1915 recalls a horrific scene from earlier days: Near the site of the small house along the Turnpike at the County Home was a log shed much resembling the open sheds used for the sheltering of horses built at taverns in the country and at country churches. It was nothing more than a shed with a roof, back and sides. The front was open. Here both the sick, aged and insane were confined. The insane were chained with heavy chains and attached to heavy iron balls. The chain and ball system of preventing their escape and injuring other persons was then used.-Miss Catharine Byerly (via schuylkillhavenhistory.com) The almshouse expanded several times by adding a building for the elderly in 1859, a building for the insane in 1869, as well as a bakery and laundry buildings in 1872. Efforts by Dorthea Dix and others sought to eradicate the almshouse system by moving the mentally ill into separate facilities specifically constructed to treat the insane. In 1911 construction began on a mental hospital on the hill behind the almshouse; the old "pest house," a building for those with cancer or venereal disease, was demolished to make way for the new institution. It opened in 1913 as the Schuylkill County Hospital for the Insane, built at a cost of $571,000 and had the capacity for 600 patients. Like state-run mental hospitals, Schuylkill County Hospital utilized a vast swath of farmland consisting of 283 acres to produce food and dairy for the residents, often using patient labor as a form of "occupational therapy." As the hospital population declined, these farming operations ceased by 1961 and all patients were consolidated to the 1912 building. The other structures were either demolished or purchased by the Penn State Schuylkill university and renovated. The facility followed a natural shift in its role from a psychiatric hospital to a nursing home (as many aspects of these fields overlap), operating under the name Rest Haven. A building was erected in 1969 to work in tandem with the older 1912 structure, however the latter was closed by the Department of Health in 1994 due to its deteriorating condition. The older structure sat vacant until it was demolished in 2010 after a fire ravaged the interior.

]]>

The establishment of Rest Haven began with the old Schuylkill County Almshouse, a single building erected in 1833. The almshouse was a kind of jail for the infirm, poor, elderly, insane, epileptic, criminals, and those with developmental disabilities - basically a place for those "unwanted" in society at that time. Conditions were atrocious, as can be imagined by housing these many types of people under one roof. A written account from 1915 recalls a horrific scene from earlier days:

Near the site of the small house along the Turnpike at the County Home was a log shed much resembling the open sheds used for the sheltering of horses built at taverns in the country and at country churches. It was nothing more than a shed with a roof, back and sides. The front was open. Here both the sick, aged and insane were confined. The insane were chained with heavy chains and attached to heavy iron balls. The chain and ball system of preventing their escape and injuring other persons was then used.

-Miss Catharine Byerly (via schuylkillhavenhistory.com)

The almshouse expanded several times by adding a building for the elderly in 1859, a building for the insane in 1869, as well as a bakery and laundry buildings in 1872. Efforts by Dorthea Dix and others sought to eradicate the almshouse system by moving the mentally ill into separate facilities specifically constructed to treat the insane.

In 1911 construction began on a mental hospital on the hill behind the almshouse; the old "pest house," a building for those with cancer or venereal disease, was demolished to make way for the new institution. It opened in 1913 as the Schuylkill County Hospital for the Insane, built at a cost of $571,000 and had the capacity for 600 patients.

Like state-run mental hospitals, Schuylkill County Hospital utilized a vast swath of farmland consisting of 283 acres to produce food and dairy for the residents, often using patient labor as a form of "occupational therapy." As the hospital population declined, these farming operations ceased by 1961 and all patients were consolidated to the 1912 building. The other structures were either demolished or purchased by the Penn State Schuylkill university and renovated.

The facility followed a natural shift in its role from a psychiatric hospital to a nursing home (as many aspects of these fields overlap), operating under the name Rest Haven. A building was erected in 1969 to work in tandem with the older 1912 structure, however the latter was closed by the Department of Health in 1994 due to its deteriorating condition. The older structure sat vacant until it was demolished in 2010 after a fire ravaged the interior.

]]>

The Recordação (The Rememberance) was built in 1961 in Arrentela as a passenger ferry between Cacilhas and Terreiro do Paço. The fleet of boats that connected the two banks of the Tagus River were known as cacilheiros (named after the town of Cacilhas), and played a vital transportation role until a bridge was constructed in 1966. The Recordação was the last cacilheiro to be constructed of wood, as plenty of it could be found in the country and it was much cheaper than steel. At 82' (25m) long, she weighed in at 85 tons and was powered by a single 525 horsepower engine. The vessel could accommodate 518 passengers and 4 crew, with a top speed of 10 knots. It sailed the Tagus for over twenty years for the company Transado until being sold to the town of Setúbal, and eventually being abandoned on a beach in an industrial zone in 2007.

]]>

The Recordação (The Rememberance) was built in 1961 in Arrentela as a passenger ferry between Cacilhas and Terreiro do Paço. The fleet of boats that connected the two banks of the Tagus River were known as cacilheiros (named after the town of Cacilhas), and played a vital transportation role until a bridge was constructed in 1966.

The Recordação was the last cacilheiro to be constructed of wood, as plenty of it could be found in the country and it was much cheaper than steel. At 82' (25m) long, she weighed in at 85 tons and was powered by a single 525 horsepower engine. The vessel could accommodate 518 passengers and 4 crew, with a top speed of 10 knots. It sailed the Tagus for over twenty years for the company Transado until being sold to the town of Setúbal, and eventually being abandoned on a beach in an industrial zone in 2007.

]]>